Want more freedom? Hold your bandhas!

Want more freedom? Hold your bandhas!

“To stand upright is to work against gravity, an if this resistance to the pull of gravity is defined as the force of life, it can be said that those who expend the least amount of effort in holding a vertical posture have the greatest potential to direct their life energies toward some other activity.”

-Zen Imagery Exercises by Shizuto Masunaga

Patthabi Jois was on to something when he said “squeeze your anus.” Mula Bandha and Uddiyana Bandha are two key bandhas for supporting both a strong physical practice, such as done in the Ashtanga Vinyasa method, and your normal daily activities. But why do they do that, and how do they help?

In this article, we’ll explore Uddiyana Bandha and its anatomical link, Transverse Abdominis.

So what is Transverse Abdominis (T.A.)?

How do we find it?

What does it actually support?

First, the anatomy:

We have several layers to our abdominal wall: rectus abdominis, internal obliques, external obliques and, deepest of all, transverse abdominis. Most of the time when we attempt to find support through our core, it comes from the outer laters of our abdominal wall, rectus abdominis, or as some people refer to it, the “six pack” muscle. This is a great muscle for curling the torso forward or helping to lift the legs, but it’s not so great for supporting the spine for two reasons:

1. It’s on the outside! The front of the spine is the true core of the body, and in between rectus abdominis and the front of the spine are other muscles, organs and fascia. So how is a muscle that’s so far away from the spine supposed to help support it? In short, it can’t. At least not efficiently.

2. It’s not meant for long-term support. It’s meant for short-burst activation, such as when lifting heavy objects, curling the torso forward or lifting the legs. Anatomically, it’s position is quite ideal for these actions, and the type of muscle fibers support this.

Transverse abdominis runs deepest of the core muscles, and is a much more efficient muscle for stabilizing the spine.

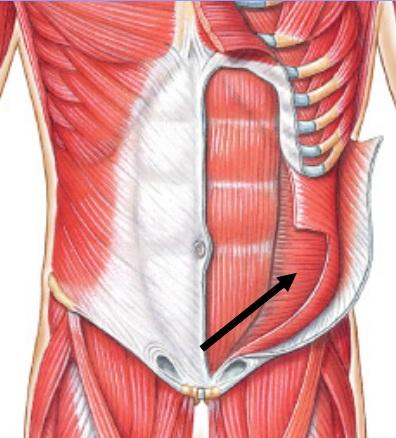

This picture does a great job of visualizing the layers of the abdomen, with the arrow pointing to T.A. As you can see, it runs deep to the other layers on the front, with its fibers running left-to-right instead of up-and-down.

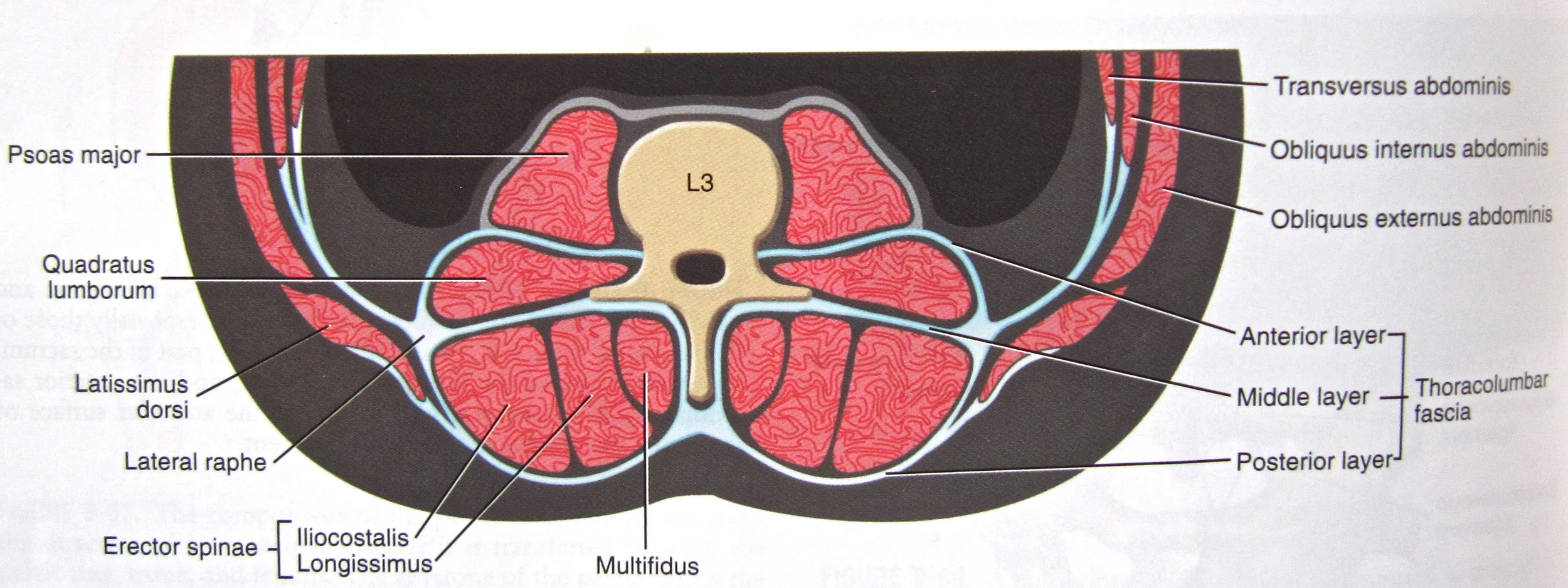

It also wraps around the back, attaching into the thoracolumbar fascia:

In this image, the fascia is the white layers in between the muscles. As you can see, the thoracolumbar fascia had three layers: it wraps around the back of the back (towards the skin), the middle of the back (transverse process of the vertebrae) and the body of the spine. So, one can imagine that this would be the ideal muscle for supporting the spine. Much better than the six-pack muscle, which is so far off you can’t even see it in the picture above.

Transverse Abdominis and the muscles of the spine

Here’s an interesting note: look again at the picture of the layers at the back above. Notice how the fascia that T.A. is attached to also wraps around the front of the psoas, in between quadratus lumborum and around all of the erector muscles. Fascia is highly innvervated, meaning it carries a lot of the communication network of the body. Since the fascia of T.A. and the fascia of the spine muscles are so closely linked, when you use T.A., your body automatically knows by association that it should use the other muscles around the spine as well. Truly, everything in the body is connected, so if we can find the correct muscles to activate (or the right way to activate them), the inherent genius of the body will take care of the rest.

How do we find it?

If you already know and practice Uddiyana Bandha, then great. If not, there are several ways to find uddiyana bandha and transverse abdominis. One of the easiest ways to feel on yourself is sitting on a chair or bench. Place one hand on your belly, and let your other arm relax. Now, very slightly pull in your belly. It should be 5-10% of your maximum effort. See if you can feel a difference between the outside muscles (rectus abdominis and external obliques) and the deeper muscle transverse abdominis. This would feel like the difference between flexing your six-pack versus slightly pulling the belly in.

Now, let’s try another approach: reach your tailbone down into the floor, chair or bench, and reach the top of your head up towards the sky. In this position, it will be easiest to have your eyes towards the horizon. Can you feel the core slightly activate when doing this? That’s another approach to finding deep core activation, also known as palintonicity.

So what does this actually support?

In short, the spine. As we saw earlier, it wraps all the way around the core of the body, and the fascia it connects to communicates directly with the muscles that are directly attached to the spine. This does several things:

1. It tells what spinal muscles to contract and when in order to stabilize the spine.

2. It provides stability for movements engaged from the core.

3. It maintains a proper level of intra abdominal pressure.

Pattabhi Jois stated that Bandhas are energetic locks. So how does our anatomical activation relate to energetic locks? To provide one explanation for this, let’s return to our meditating compatriots from the Zen tradition:

“To stand upright is to work against gravity, an if this resistance to the pull of gravity is defined as the force of life, it can be said that those who expend the least amount of effort in holding a vertical posture have the greatest potential to direct their life energies toward some other activity.”

-Zen Imagery Exercises by Shizuto Masunaga

If the force to resist gravity is a creative force, or the “force of life,” then by providing more intrinsic structural support, we are freeing more energy to use for things other than resisting the pull of gravity. Thereby, these locks are energetic - keeping the energy in instead of letting it be expended.

So hold your bandhas! You’ll be much more free.