What does being "tight" really mean?

What does "tight" mean in the body?

More often that not, I hear clients report that areas are "tight". It's an incredibly common description, and often goes along with areas that are "sore", "stiff", or otherwise just painful. So what does "tight" actually mean? And what can we do about it?

Tightness is a sensation

First, let's get a few descriptions down. Tight, as most people mean it, is a sensation. There's no true biomechanical term in science that describes being "tight"; instead, it is purely a response to what's happening in the muscle itself.

People often assume if something feels tight, it must also be short. And going along that line of thought, if something is tight (and therefore short), it needs to be lengthened, whether that's from stretching, Rolfing or mashing it with a foam roller.

However, the feeling of tightness may or may not correspond with something actually shortening in the muscle. And in fact, it's often the opposite: often times, people feel the sensation of being tight not because something is too short, but because it's over-stretched or simply over-worked. Remember, tightness is only a sensation.

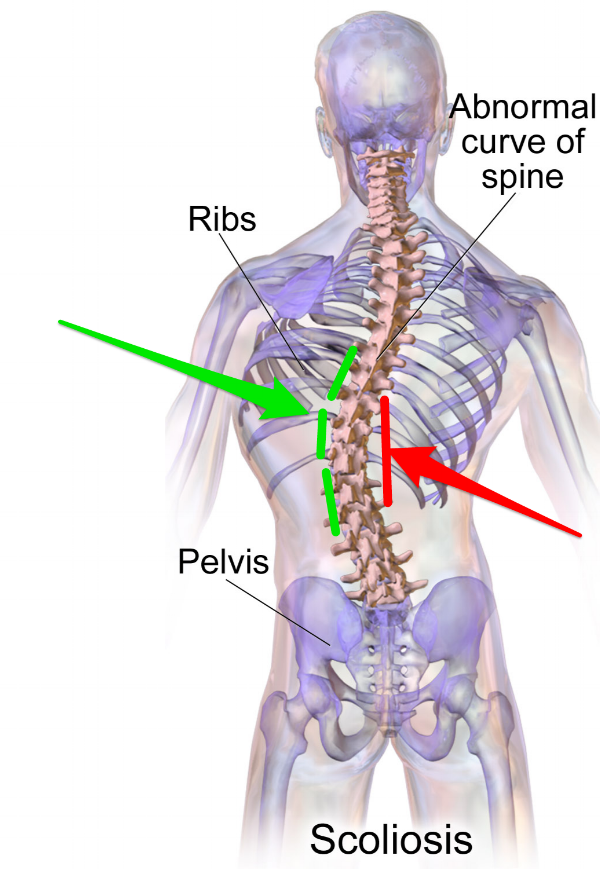

Let's use scoliosis as an example. Check out the image below, and see what you think.

I see lots of people with scoliosis, and more times than not, where they report feeling tight (the green area) is not where they actually have the tightness (the red area). They feel the green side, the outside of the curve, because that's the side that's being stressed, over-stretched, over-worked. However, if you think about it in a literal sense, the area that is really the tight side is the red side, the inside of the curve. But almost no one mentions that.

This is not to say that people are misled about what's going on in their bodies, but simply that sensations can often be confusing. Ida Rolf used to always say (and I'm paraphrasing here), "Where it hurts it ain't!" And this is exactly what she meant by that. Even though it hurts on the over-stretched, over-worked side, and even though it may feel good to work along that side, what's going to create better balance in the long run? Working the already over-stretched side, or working the side that truly is tight (but may not hurt)?

That's why more often than not in Rolfing we work "where it ain't." That is to say, we work the area that may be sore to help calm it down, help it relax, but we also work the area that is more truly "tight" in order to help correct the pattern that's causing the painful sensation, or causing the muscles to be over-stretched and over-worked in the first place.

Let's use another quick example: tightness or pain between the shoulder blades. When I hear people talk about this, I first look for two things: rolled forward shoulders and forward head position. Why? Because more often than not, pain between the shoulder blades is caused by the same idea as with the scoliosis above - it's not that the muscles between the shoulder blades are honestly too tight, but rather they're over-stretched and/or over-used. So therefore, by working both the muscles of the shoulder blades themselves and the muscles of the chest and neck, the body doesn't need to keep sending the sensation about the shoulder blades being "tight".

Ahh, body balance. Isn't it a beautiful thing?

As always, I'm open to chat about any questions you may have. Rolfing, body balance, anatomy, or what you can do on your own. Hit me up: michaelblackrolfing@gmail.com